News

One Fall 2023 section of “ES96: Engineering Problem Solving and Design Project” worked with client BASF on strategies to reduce plastic production and increase recycling efforts

The United States generates millions of tons of plastic waste every year. That waste is worth potentially billions of dollars, but the majority of plastic just winds up in landfills, where it produces significant greenhouse gas emissions and not much else.

Companies like BASF, one of the largest petrochemical and plastic producers in the world, have both financial and climate-based incentives to invest in programs that recycle, reuse, and recirculate plastic products. BASF partnered with students at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciecnes (SEAS) last fall to map out the current state of U.S. and international plastic recycling programs. BASF was the client for a section of “ES96: Engineering Problem Solving and Design Project,” a core course for third-year SEAS students pursuing S.B. engineering degrees.

“We wanted the students to become more aware of how complex these issues are, with the hope that one day they can contribute in even more meaningful ways than the class project and feedback to BASF as the client,” said Tom Holcombe, Head of Collaboration & Scouting North America at BASF. “Perhaps this ignites a spark of curiosity that leads into a career around creating industrially scalable solutions, industrial policy, or just moving the needle a little bit in a direction that benefits people and the planet.”

When tackling a challenge as broad as optimizing plastic recycling, clearly defining specific problem statements and solutions is key. The ES96 section, taught by Kelly Miller, Senior Lecturer on Applied Physics, ultimately chose three focus areas: an interactive map with key information related to landfills and recycling; a case study into the reusability of polyurethane foam; and an overview of companies offering take-back programs for various plastic products.

“Everybody turned in a problem statement related to something that had been discussed during the client presentations,” said Cooper Knarr, a project co-lead and mechanical engineering concentrator. “We then came to class and pitched our ideas, which was really helpful. It was a full session of researching what the problem statement could be, thinking about key words the client said multiple times, and researching circularity and plastics and what the current state of the industry looks like.”

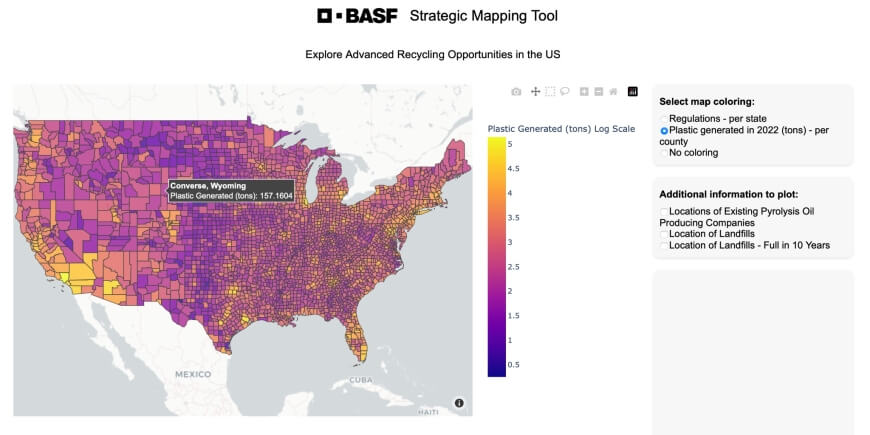

The student-designed mapping tool displays a range of data related to landfills and recycling in the United States, such as tons of plastic generated per county

Knarr’s group built the map using plastic recycling data. The map indicated landfills around the country, including their fill rate and estimated closure date, as well as the amount of plastic waste produced per region and current recycling policies. This data was then cross-referenced with companies that produce pyrolysis oil, a by-product of the recycling process that can in turn be used to manufacture new plastics.

“We went into the map with the goal of giving something that was flexible, easy to use, and could be adjusted to their needs,” Knarr said. “Pyrolysis oil companies need a consistent and reliable plastic supply, so using this map, BASF could identify whether or not a company would be suitable for them.”

Pierce Cousins, a bioengineering concentrator and project co-lead with Knarr, was part of the group that tested the reusability of polyurethane foam, a common component in BASF products. They demonstrated that recycled polyurethane foam both costs less and produces less CO2 emissions than new products, and that the recycling process doesn’t significantly compromise the strength of the foam.

“Instead of trying to return it perfectly to the foam you had before, which is extremely energy-intensive and not practical for CO2 emissions, our process creates a simple downgraded product that could extend the life of any urethane product BASF produces,” Cousins said. “We wanted to showcase that efforts to recycle these products shouldn’t be completely ignored, that there’s still use for secondary products.”

The third group highlighted a number of companies with plastic take-back programs. Partnerships with companies close to BASF recycling facilities could produce a reliable supply of plastics such as nylon fishing nets at the end of their lifecycle. BASF could then shred and reprocess the nets into new vinyl yarn, which could in turn produce new nets ready for use.

“The students exceeded expectations and we’d love to work with the app they developed around geographies and policies for where pyrolysis companies could be located,” Holcombe said. “This is also helpful to better understand the possible waste streams for recovery more generally, and the depth of research that the students performed in that pillar of the project was exceptional.”

ES96 projects are frequently the largest class projects SEAS engineering students work on in their first three years. Along with specific technical or research skills, students also learn how to work within a team comprised of individuals with diverse engineering concentrations, backgrounds, work styles and personalities.

“How you manage tasks, how you manage time, how you understand how everyone works, is important,” Knarr said. “I definitely learned how to better understand people, and how important that is to a design project.”

Cousins added, “The thing I got the most from the class was interpreting it as an engineering consulting class rather than an engineering materials class. That helped me, because now I know that sometimes you’ll have a client that will want something very broad fixed, but have no general plan for it and might need multiple ideas. We had to learn to adapt to a changing client. It was nice to learn to be on your toes, and to create something you could present.”

This is the third time BASF has been the client company for an ES96 section since launching the BASF Advanced Research Initiative at SEAS in October 2007, which later evolved into the North America Open Research Alliance. Previous sections worked with BASF on removing microplastics from drinking water and improving access to carpet recycling programs.

Topics: Academics, Environment

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Matt Goisman | mgoisman@g.harvard.edu